"By virtue of his discoveries, Louis Vicat gave the builders of the 19th century free license for the wildest audacity." Honoré de Balzac

In 1812, as a young graduate of the Polytechnique and École des Ponts et Chaussées engineering schools, Louis Vicat (1786-1861) was sent to Souillac in southwest France to build a bridge over the Dordogne River. There he developed an interest in the mechanism by which hydraulic binders set in water.

In 1817 he published the results of his research into hydraulic phenomena affecting lime and cement. The discoveries of Louis Vicat, recognized by France's Royal Academy of Science, prove that the manner in which a hydraulic binder sets when in contact with water is governed by the proportions of fired clay and limestone it contains.

The man and the engineer

His history

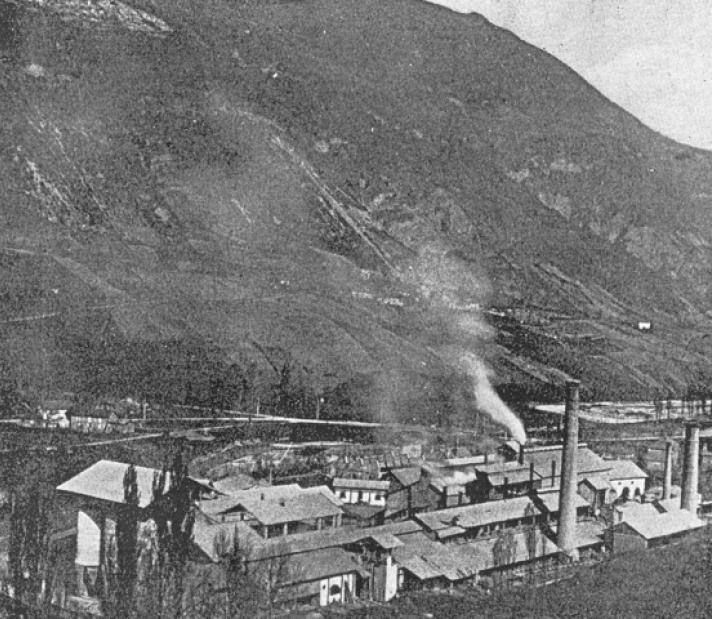

Louis Vicat revealed the secrets of artificial cement in 1817 while building a bridge over the Dordogne River, between Souillac and Lanzac, in southwest France. He filed no patent and freely give advice to the architects and contractors of his time. His discoveries led to the development of the industrial manufacture of cement in the 19th century.

Louis Vicat was born in Nevers (central France) where his father, a non-commissioned officer in a regiment of Royal Piedmont Dragoons, was garrisoned. When his father's military career was over, the family moved to Seyssins, near Grenoble.

Louis Vicat enrolled at the École Polytechnique engineering school and graduated as an engineer of the Ponts et Chaussées school in 1809.

Louis Vicat was assigned a mission in Souillac, in southwest France: building a bridge over the Dordogne River. Its construction was to take over 10 years, for State funds were absorbed in the Napoleonic wars. This left him the time to find a solution to the problem of the low quality of the limes used in that period.

Louis Vicat published an article in a scientific journal—Les Annales de Chimie—in which he presented his discoveries about the hydraulic phenomena of lime and cement, i.e. the ability of lime to set under water. His discovery concerned the right proportions of clay and limestone to achieve the desired result.

France's Royal Academy of Science validated Louis Vicat's discovery. He chose not to file a patent since he considered he owed the community at large for his academic and scientific training.

Louis Vicat was awarded the title Knight of the Legion of Honor. His life's devotion to the science of cement received national and international recognition. He entered the prestigious French Academy of Science in 1833.

Louis Vicat was appointed Inspector-General of the Ponts et Chaussées. His son, Joseph Vicat, founded the company Vicat.

Louis Vicat died. In 1889, he was one of the 72 scientists, engineers, and industrialists whose names were inscribed on the Eiffel Tower in recognition of their work or discoveries that honored France between 1789 and 1889.